Education in the Era of ChatGTP

“Give me recycling, or give me waste!” declares a student at the front of the Little Theatre. The class is speech and debate; the assignment is to give a speech in the style of a historical figure (in this case, said figure is founding father Patrick Henry).

Of course, Patrick Henry didn’t write this speech. But the student didn’t write it either: nobody did. Instead, he generated it using ChatGTP, an artificial intelligence software that generates text based on written prompts provided by users.

ChatGPT can analyze Shakespeare, explain the 2008 housing crisis, and write Harry Potter fanfiction. It can “remember” feedback and rectify its mistakes (which are frequent; the program has been criticized for its tendency to falsify information). And most importantly, it can produce complex prose nearly indistinguishable from that of a human being. A number of companies, including Google, Microsoft, and WeChat, have rushed to launch rivaling versions of the product, albeit to less success.

What makes ChatGTP different from previous iterations of the chatbot is that its knowledge, unlike that of its predecessors, is self-sustaining and perpetually expanding. ChatGTP is a large language model, or, in simpler terms, a very advanced autocomplete tool: it ‘trains’ itself on a vast diet of text pulled from both the Internet to predict its own next word.

Understandably, this technology has sparked both widespread fascination and alarm. But nowhere has its impact been more deeply felt than in the classroom, where many fear that its ease of use, encyclopedic knowledge, and ability to mimic human speech will result in mass cheating, if not a deterioration in students’ writing and critical thinking skills. Some are even calling it the end of high school English.

“Students are already using it. Whether we want them to, think they are, believe that they are… it’s out there,” said speech and debate instructor Amy Gregory. “And trying to suppress it would be like someone suppressing the electric typewriter. If you don’t change with the times you get left behind.”

Although Gregory calls her decision to bring AI into the classroom a matter of self preservation, not everyone has been so willing to embrace the nascent technology. The Los Angeles Unified School District blocked ChatGTP from all school devices in mid-December, citing concerns over academic honesty. New York City Public Schools made a similar move two weeks later.

At Sedro-Woolley High School, there is no indication that an AI ban is underway. In the past few months, however, educators have been engaged in faculty-wide discussions about how to properly address the technology.

“I don’t think a lot of teachers are taking it as seriously as the students are,” Gregory said. “And again, that’s to their own detriment. Because it’s like a whack-a-mole, but it’s not just coming up the top. It’s coming out the sides. It’s coming out the back. So if we’re trying to contain it, it’s going to crush us.”

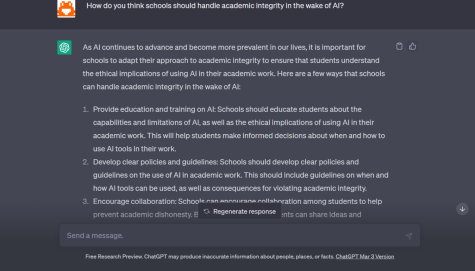

This idea — that educators should learn to work with AI and not against it — seems to be a prevalent one among faculty at SWHS, many of whom are beginning to incorporate the technology into their instruction. In English 102, for instance, educator David Shusta is using AI as a platform for ethical discussion.

“Our first argumentative writing assignment [was] to take a look at what plagiarism is, define that in a historical context for academic writing courses, particularly in college, and then consider the use of this artificial intelligence, which tries to mimic human thought and writing patterns,” Shusta explained. From there, he said, students were tasked with proposing a new class plagiarism policy: one that takes the issue of AI into account.

Sedro-Woolley High School’s handbook defines plagiarism as the act of “knowingly submitting another’s work as your own.” Central Washington University, which provides credit for some courses offered by SWHS, defines it as “taking and using as one’s own, without proper attribution, the ideas, writings, or work of another person in completing an academic assignment.” Under these policies, submitting work generated by AI wouldn’t qualify as a punishable offense, since both assume that plagiarism involves the unattributed work of another human being.

These are the types of inconsistencies that educators say will likely need to be addressed as the technology becomes more of a concern. Alice Daily, chair of the Academic Integrity Program at Villanova University, says in an article for WIRED that “students who commit plagiarism often borrow material from a ‘somewhere’— a website, for example, that doesn’t have clear authorial attribution. I suspect the definition of plagiarism will expand to include things that produce.”

Shusta plans to utilize the insights presented by students in school and district-wide discussions of potential modifications to plagiarism policy. So far, however, no such large-scale policy changes have been adopted.

“There are now conversations going on about the technology in other departments,” he said. “I think it’s now on the district’s radar, so they’re paying attention to it, but I think they’re seeing, you know, how are we going to handle it? And so that’s where our assignment comes in.”

The process of grappling with these ethical concerns in the classroom will likely last several years, especially as the technology continues to develop. But in the meantime, some software companies have been working on more immediate solutions to the issue of plagiarism. In January, Princeton University student Edward Tian made headlines when he released GPTZero, an app designed to detect when a text is AI-generated. But programs like these (of which there are plenty) are far from foolproof.

“Right now, what [the software detectors] do is spit out a percent probability or likelihood that something was generated by a bot. But it’s not conclusive,” said Shusta. “Whereas in past years and semesters, I can actually find the source the student used, and I know with hundred percent certainty that the student lifted information and didn’t give credit. I’m not comfortable with 65%, 85%, even 95% probability. It’s possible that the student actually made [the text]. And so that software is problematic.”

Other methods of detection may prove equally flawed. OpenAI, the company that developed ChatGPT, recently flirted with the possibility of embedding digital “watermarks” into text generated by the program. However, experts note that watermark-free imitators of ChatGTP will almost certainly make their way onto the market as the technology advances.

Rather than relying on external methods of detection, both Shusta and Gregory stressed the importance of becoming familiar with how their students write.

“I see so much writing by my students that I know how they sound,” Shusta explained. “I know their style and their voice, and then I see something that’s shockingly different and that makes me think, okay, where did this come from?”

Both Gregory and Shusta are also beginning to experiment with new methods of instruction and evaluation: ones that can’t be cheated by simply dropping a prompt into ChatGTP.

“To sort of squash the fears of so many professors and teachers around the country, I think we could reword or make the requirements different for various kinds of assignments, so that at least some of the research the students do [has] to be authentic,” said Shusta. “If they have to, say, use scholarly journal sources, that’s really going to cut into what ChatGPT can currently do.”

When asked how she might safeguard against plagiarism in her creative writing classes, Gregory said that she plans to incorporate more handwritten and in-class assignments into her curriculum. She also plans to begin asking students to orally discuss their work with her.

“If the final product includes a ton of things that I have not seen any evidence for anywhere else in the entire semester, then we can have that conversation,” Gregory said. “Whenever a student can talk about their own writing or their protagonist or their characters, you know they own it, you know it’s theirs. When they have really no idea and can’t really remember what they said, there’s doubt.”

Even prior to the arrival of ChatGTP, educators across the country have been sounding the alarm over the future of the humanities. And this concern is far from unjustified: collegiate study of English and history dropped by a third between 2011 and 2021, and humanities enrollment overall has dropped by seventeen percent nationwide, according to a study by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

There are a number of factors contributing to this decline, but teachers seem to agree that there is a disconnect between students and humanities education as it exists today, especially in a culture that prizes STEM and vocational-focused education above all else. When separated from the context of their purpose — to bolster critical thinking and communication skills — the common conventions of high school English class, such as crafting a thesis statement or assembling a five-sentence paragraph, have begun to feel rote and meaningless, inapplicable to the lives of today’s teens.

But some teachers hope that the emergence of AI, by way of necessity, might change that.

“What is it that we want? Do we want a well-crafted five paragraph essay, or do we want them to be making personal connections to the written word? It’s two very different things,” said Gregory.

In the past, she continued, it was hard to do one thing without the other. But things have changed.

“Now, you can write a five paragraph essay on the symbolic meaning of the green light in Great Gatsby, and it’ll be brilliant and it’ll be one of a kind, and it will be AI generated,” she said. “AI cannot make a personal connection for a student. Everybody has a green light in their own life. To talk about that would be much more powerful than just regurgitating something that’s already been explored.”

Assigning more personal writing would make it much harder for students to cheat, Gregory continued. She is currently considering converting her creative writing class to a course on autobiography.

But teachers at SWHS aren’t only changing what they ask students to write; they’re also beginning to change how they ask them to write it.

“Instead of focusing on the brainstorming or the initial generation of a draft, we could focus more on the development of ideas through sources and more of the revision process,” Shusta said. “A lot of students get hung up on and then ultimately don’t do or don’t finish assignments because they don’t know where to start. So maybe we initially use this as a starting point to get us going, to get us thinking. But ultimately, I want to know what my students think, not what the computer thinks.”

According to Gregory, AI might also serve as a valuable aid to the revision process.

“A student in creative writing had 750 words and one paragraph, no formatting, no punctuation,” Gregory said. She recommended that the student run the paper through ChatGTP. Together they sat down and observed as the program edited the text, sentence by sentence, in real time. “And he’s like, ‘oh, you put a comma there?’ And he was narrating it out loud kind of as we were sitting here. So there could be benefits that way. You know, instead of expecting to do peer editing, [where] you sit there and you have to grind through all these words, let the machine take care of that part and then you can really focus on the ideas.”

There is no doubt that adaptations to curriculum will be necessary as this technology continues to evolve. But critics argue that using AI to help students write comes with its own set of caveats.

“I think the whole logical process of having to put together a formal essay is a really worthwhile exercise in organization, and thinking, and logical thought, and arranging an argument,” said Christopher Jensen, who teaches AP Calculus at SWHS.

“There’s been so much movement in education to just go, ‘oh, grammar and punctuation, those things are just overemphasized. Let them express themselves.’ But no. I disagree,” he continued. “I think if we want to actually communicate, let’s do it correctly. Everybody can learn it.”

Essentially, opponents are concerned that the “grunt work” that ChatGTP aims to eliminate — the tedious act of figuring out what to say and how to say it coherently — is in fact inherent to the value of writing. If the process of translating an idea into words is grueling and at times outright frustrating, it’s because writing requires a level of dynamic, reflexive thought that is lost once automated. And with that loss, they fear, comes a decline in reasoning and critical thinking skills.

“Having an idea, composing it into language, and checking to see whether that language matches our original idea is a metacognitive process that changes us,” write Chris Gilliard and Pete Rorabach in a recent article for Slate. “It puts us in dialogue with ourselves and often with others as well. To outsource idea generation to an A.I. machine is to miss the constant revision that reflection causes in our thinking.”

“There’s a point where it becomes not just an aid to understanding and learning, but a replacement for understanding and learning,” Jensen concluded. “I think that’s where the problem is.”

It’s important to note that this is not the first instance in which educators have had to grapple with changes brought about by a revolutionary technology. When Casio introduced the first ever commercially available calculator in 1985, the concerns about its implications for academic integrity in the classroom were remarkably similar to those faced today.

“I think the biggest thing with the calculator is, it might have been a time when the answer was the important thing,” said Jensen, who was teaching when the graphing calculator first became readily available. “Now it’s much more — which is a good trend in education — how you get the answer. It’s showing your work, showing the steps. So I think you have to put the emphasis of the points and things in your grading on that [display] of understanding, than actually just on the answer, in the end.”

Today, Jensen allows students to use calculators and algebra systems like Photomath and Mathway on homework. However, he also gives homework much less weight in comparison to work produced in-class, such as tests.

It’s difficult to ignore the parallels between the response to calculators and ChatGTP. In both situations, educators have had to change how they teach in order to prevent being cheated by technology. And in both situations, these educators have used this shift as an opportunity to move toward instructional methods that prioritize deeper comprehension over rote memorization.

Whether or not AI will bring about this evolution is only a matter of time.

“I was a student when calculators came out. And I’m sure there were math teachers that thought that was gonna be the end of competency for doing arithmetic by hand. And it’s a tool now that we use all the time. No different than the slide rule being a tool of the earlier generation,” Shusta concluded. “We’re gonna have to find a way to use [ChatGTP] in a meaningful way that doesn’t take away from our overall goals of wanting students to think for themselves and express those thoughts in a coherent way through writing. And if ChatGTP is a tool to facilitate that, okay. But I don’t want it to replace student thought.”